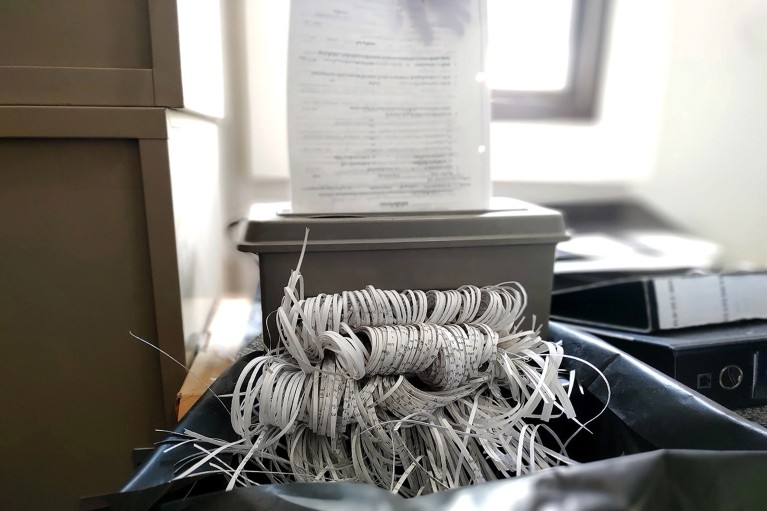

Misconduct is the main reason journal articles from India are retracted.Credit: sritakoset/Shutterstock

India’s national university ranking will start penalizing institutions if a sizable number of papers published by their researchers are retracted — a first for an institutional ranking system. The move is an attempt by the government to address the country’s growing number of retractions due to misconduct.

These universities have the most retracted scientific articles

Many retractions correct honest mistakes in the literature, but others arise because of misconduct. India has had more papers retracted than any country apart from China and the United States, according to an analysis of the public database maintained by Retraction Watch of retractions over the past three decades.

But whereas less than 1 paper is retracted for every 1,000 papers published in the United States, more than 3 are retracted for every 1,000 published in China, and the figure is 2 per 1,000 in India. The majority in India and China are withdrawn because of misconduct or research-integrity concerns.

Retractions are “a very important signal of misconduct, and we should be looking closely at them now”, says Achal Agrawal, a data scientist in Raipur, India, who was involved in the analysis. Agrawal is founder of India Research Watch, an online group of researchers and students who highlight integrity issues.

Some researchers have welcomed the government’s decision, calling it a first step in acknowledging and attempting to tackle the problem. But others warn that retractions are a way for science to self-correct and should not be penalized.

The policy’s effectiveness will depend on how exactly institutional retractions are measured and penalized — details that will be revealed only when the latest ranking results are announced, in a couple of weeks.

“I hope that the penalty is strong enough to act as a deterrent, and it doesn’t remain symbolic,” says Agrawal.

Moumita Koley, who studies metascience at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, also appreciates the policy. “Indian science needs a little clean-up, and this shows that people have taken note,” she says. But she worries that the situation won’t change for the better. She says that adjusting one ranking instrument doesn’t remove the incentives that drive researchers and institutions to publish lots of papers at the cost of quality, such as promotions and other ranking metrics rewarding high publication counts, and individual drives for public recognition.

Rising retractions

India’s National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) assesses higher-education institutions every year. It takes into account factors including teaching, engagement and research-impact metrics such as publication and citation counts.

“It’s the most important ranking in India,” says Agrawal. Institutions must participate in the ranking to be eligible for certain national grant schemes. A high rank confers some advantages, including permission to design their own curriculum.

But the growing number of retractions in India and globally has not gone unnoticed, says Anil Sahasrabudhe, who chairs the National Board of Accreditation in New Delhi, which conducts the national ranking. A 2025 analysis by Nature found that several Indian institutions were among the top global institutions with the most retracted papers in the past five years.

The board decided to deduct marks as a way to ‘name and shame’ institutions, and send the message that unethical research practices are not acceptable, says Sahasrabudhe. Because this year will be the first in which the assessment considers retractions, penalties will be mild and symbolic for now, he says.

The NIRF will count the number of research papers retracted in the Scopus and Web of Science databases for each institution over the past three years, he says. A small number of retractions is acceptable, but generally, “the more number of retractions, the more the penalty”. Institutions that consistently get many retractions could be penalized more over time and might even be barred from the ranking, he says. Sahasrabudhe acknowledges that retractions sometimes occur for reasons beyond a researcher’s control, but when they happen in large numbers, “they are not necessarily by error but deliberate, hence need to be punished to send a strong signal.”

Root of the problem

Researchers say the assessment should also consider retractions recorded in the public database maintained by Retraction Watch, which is more comprehensive than Scopus or Web of Science and includes the reasons for retractions. Anil says they wanted to use the same source for retractions as they use for publications and citations.

Researchers also say the ranking should penalize only those retractions that are attributable to plagiarism, fraud or other research-integrity issues — and should look for patterns of bad behaviour, as opposed to one-offs.