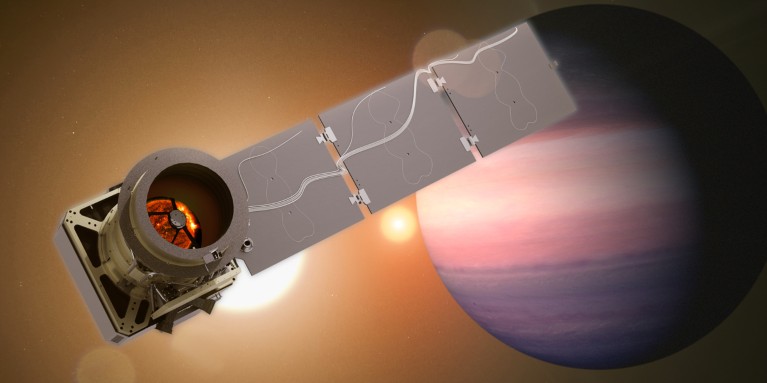

Pandora’s launch marks a first for many of the scientists and engineers involved in the mission.Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

On the morning of 11 January, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket blasted off from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California to send NASA’s latest telescope into orbit. As the satellite, named Pandora, was released from its launch vehicle, “we were all in tears”, says Ben Hord, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who’s been working on the mission for about four years. “It’s strange to see your co-workers cry, but in that moment, it just made sense.”

Pandora is the first satellite of NASA’s Pioneers Program to ascend into space. There are four satellites among the seven current Pioneers missions, each with a budgetary cap of US$20 million — just a sliver of the funds typically awarded to flagship missions such as the $10-billion James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The projects will address more-focused questions than larger missions; Pandora, for instance, will zero in on some 20 exoplanets and their host stars to learn more about the planets’ atmospheres.

But for Hord and other team members, Pandora marks another first: it’s the first spacecraft launch of their careers, a rite of passage for the up-and-coming team. Because of their smaller scales, the Pioneers missions present a wealth of opportunities for early-career researchers, and Pandora’s staff list is scattered with recent graduates. A statement from the University of Arizona in Tucson — where mission operations are based — says that more than half of the mission’s leading scientists and engineers are early in their careers. This is “really unheard of elsewhere in the NASA mission space”, Hord says.

Sorting starlight

Hord began working part-time for Pandora as a PhD student in 2022; this eventually led to a postdoctoral slot on the team. Working alongside more established mentors over the years, Hord says he’s learnt what it takes to run a mission and has taken on more responsibilities than he ever anticipated along the way. “I am in the room saying, ‘No, we need to look at these planets if we want to meet our mission requirements’,” he says. “People talk about having a seat at the table. I think that Pandora has taken a step further and helped early-career people be involved in choosing the menu of what we’re eating at the table.”

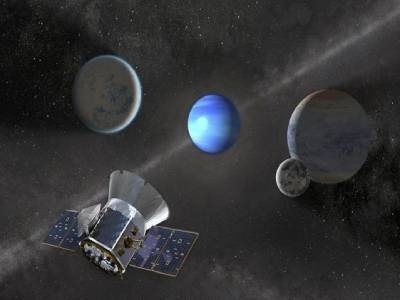

NASA exoplanet hunter racks up bizarre worlds and exploding stars

Rae Holcomb, a postdoc at Goddard who also joined Pandora as a graduate student, worked with Hord and other early-career scientists to select the targets Pandora will focus on. By looking at each star and its exoplanets for lengthy, 24-hour stretches, the goal is to tease apart the chemical fingerprints of the planets and stars. Pandora will specifically help to determine whether planets have signs of hydrogen or water in their atmospheres.

“These are really essential operations. If we pick the wrong star to look at, we have to throw out that observation, and everything slows down,” Holcomb says. “But nobody had any reservations about saying, ‘You guys understand the mission. You understand the tools. In some cases, you understand them better than the rest of us.’”